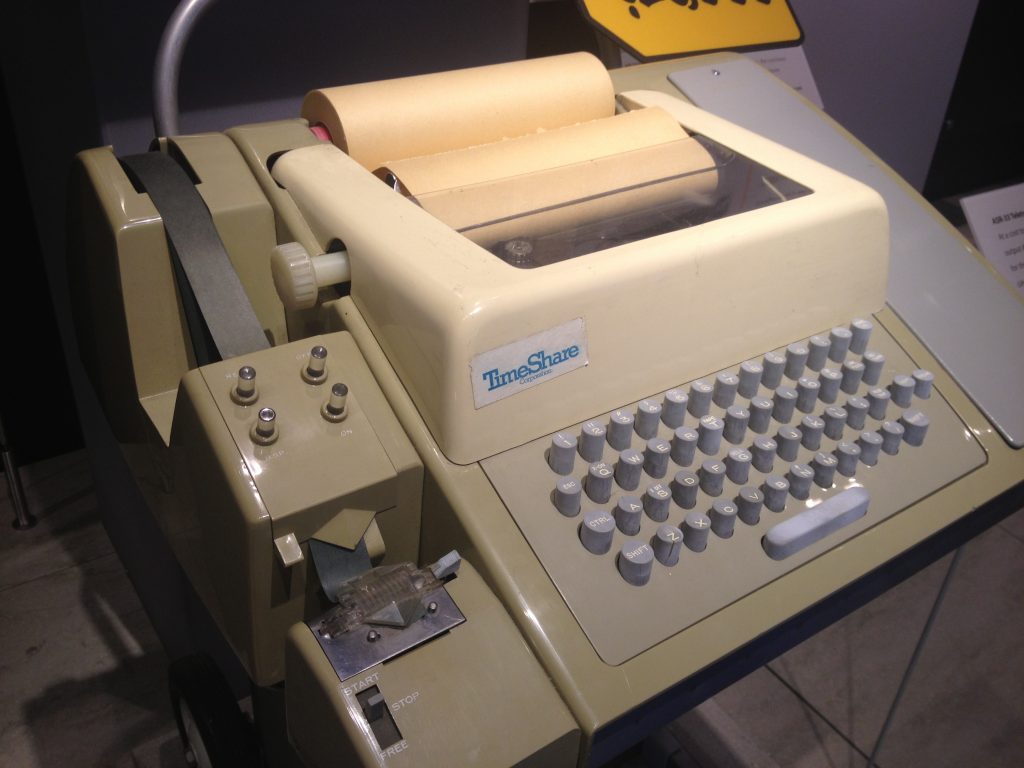

Way back we had mechanical output devices for our computers. These were big, slow, noisy and really a spill-over from the days of the telegraph, but they fulfilled their purpose and much code, including early Unix was written using them. Teletype Corporation are possibly the most well known ones of the time, although there were many other manufacturers, but when you see a picture of a mechanical printer it’s almost always a “Teletype” (And even when not, it’s almost become a generic word anyway).

Fast forward to today and we have big, fast screens and editors that do much much more than the old line-oriented editors of yester-year.

But what happens when you build a retro-style computer, running at retro speeds and you want a screen orientated editor?

Well, in the first instance, you write it, test it, use it and it’s great. In my case it’s talking to my desktop PC at 115200 baud (that’s just over 10,000 characters a second, so to fill a typical 80×25 character display takes about a fifth of a second. Acceptable. I’m also using a custom terminal program of my own making and while it’s a relatively “dumb” terminal its clever enough to only update the screen when needed, and as that update is not constrained by the speed of a serial connection it appears to be really smooth and fast, but naturally, I wanted to see what it would be like on a real (or emulated) terminal…

The 1970’s

But lets wind back some years to the mid 1970’s. Computers were still relatively slow but advances were being made in the terminal department. Mechanical printers were now up to about 30 characters per second (from the original 10) and were quieter, but were slowly being deprecated in favour of the new “Glass Teletypes”.

Glass Teletypes?

These fully electronic devices were initially limited in what they could do. Print from top to bottom, scroll upwards and… Well, that’s about it. The limitation was mostly due to the electronics at the time – Memory was still expensive, logic circuits (rather than a microprocessor) were still in-use, so it was not uncommon to see a rather large board stuffed full of TTL ICs driving the CRT (Cathode Ray Tube, often just called a “Tube” in some cultures) typically green phosphors on a black background. If you were very lucky you might have one with Orange phosphors.

Time marches on…

But nothing stays still for very long and terminals (as they were now being called) were becoming more sophisticated – under program control, the location of the cursor could be changed – some could scroll down as well as up. Partial screen clears (say from the current line to the bottom of the screen, or cursor position to the end of the current line). The net result was that “Screen Editors” could now be a thing and while programmers (initially) still used older line-orientated editors for code, ordinary users now had things like “word processors” which used the whole screen and allowed for easier editing of text for documents, letters and so on. WordStar one of those and that was first published in 1978 and relied on these new smart terminals to work.

1978 also saw the introduction of “personal computing” as we might know it today. Relatively affordable computers with screen, keyboard and storage – aimed at small businesses and serious (as they were expensive!) home users and education. The Apple II, Commodore PET and the Tandy/Radio Shack TRS-80 were the three main contenders then.

But what about the old “Glass Teletype”? They were still in-use for a long time – they were an economical device to connect to larger multi-user time sharing systems and so they lived on for quite a few years. Today they may be considered a bit of a relic. An anachronism or just something for the new kids to laugh at… (imagine a screen and keyboard with no computer!)

Retro (and vintage) Computers…

In the world of vintage or retro computers the Glass TTY is still very much a thing, so for my Ruby project I decided to see how it would work with one – although I do have a real terminal, I chose to use an emulator on my Linux desktop using the PuTTY software.

Lazy programmer…

And what I found was that over the years I’d obviously become quite lazy when it comes to screen handling. Ruby was intended to be vaguely Acorn/BBC Micro compatible when it came to screen handling – and it is, but the Acorn MOS screen handling is very much lacking in facilities required to drive a serial terminal, so while it has cursor move screen clear and scroll facilities, that’s just about it. And although there are text window facilities (to define an area not a modern “window” in a big graphical user interface) you still need to do a lot to e.g. insert a line or character or clear to the end of the line or page.. The net result was that my editor while ran quite well with my own terminal program ran rather poorly when used on a real (or emulated) ANSI terminal.

So back to the drawing board and the old days of working out screen codes, ESC [ then the magic codes. fortunately a standard had emerged which most people just refer to as ANSI. The hardest part? Making the arrow keys and command keys (Home, End, etc.) and even worse the Function keys work. It may be a standard, but there are many interpretations of that standard…

However some work on the VDU handling code in my RubyOS and in my own SDL based RubyTerm and of-course in my editor and other home grown utilities that run on the Ruby board and it’s now running as well as it might have done back in the early 80’s on a real terminal.